|

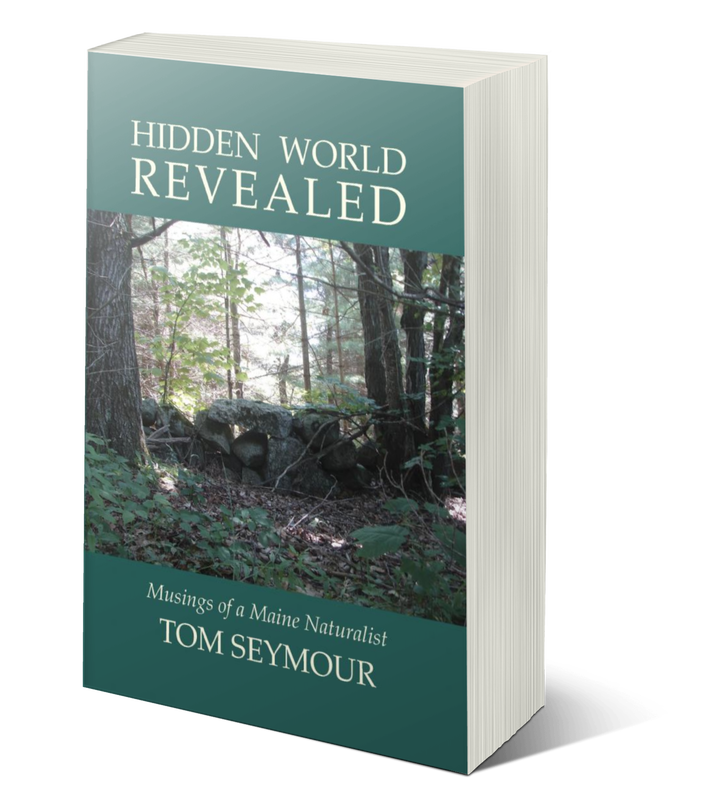

“Wild Plants of Maine: A Useful Guide (Third Edition)” by Tom Seymour

Filled with color illustrations, this book is ideal for anyone who’s new to plant identification in Maine. Seymour, an expert forager who lives in Waldo, goes into detail about each plant, including its historic and modern uses. Seymour has written several other books, including “Wild Critters of Maine: Everyday Encounters,” which was published just last year. To find these books and more Maine titles, call local bookstores to see what they have in stock and what they can order for you. Many offer over-the-phone purchasing and curbside pickup.

1 Comment

As a youngster living at home, my family ate hares several times a week, from October through March. We kept beagle dogs for running rabbits and all we ever needed to do was to walk out back, let the dog loose and stand at the ready for the short-legged hound to chase a hare past us. And then came coyotes and the rest is history. The last time I shot a hare on my woodlot was in the 1980s and since then, even seeing a bunny along the road was a special event. So you can imagine my surprise when, looking out my window a month or so ago, I spied a hare happily grazing on some clover on my lawn. I was sure the bunny wouldn’t last long, since the woods around me hold many and varied forms of predators. But somehow, the little guy survived and in time, it even became used to me and wouldn’t run when I stepped out on my tiny, front porch. This went on for some time. One day I heard a noise under my new bedroom and so went out with a flashlight to peer under the house and there was the hare, happily ensconced in the shade and safety afforded by my house. Normally, I would drive any critter away that was so bold as to live under my place. Not this time, though. I just didn’t have the heart. Then several days ago, in the early morning, I stood by my glass front door and saw the hare eating clover blossoms only four or five feet away. I watched it for some time, marveling at how it rotated its lengthy ears to listen for any signs of danger. It rotated its ears like twin radar antennae and this, too, captivated me. I tapped on the glass and the bunny looked up, saw me and went back to munching on clover. Clearly, it had become used to me. Then something totally amazing happened. Another hare, this one a bit smaller, bounced out of the nearby woods and ran up to hare number 1. Hare 1 immediately jumped in the air and ran at the interloper, driving it back in the woods lickety-split. Hare number 2 hasn’t returned, at least as far as I know. I suspect it is a litter mate of hare number 1, but of a different gender. Or maybe not. It’s hard to know about hares. With two hares living near (and under) my house, it seems a sure thing that soon, there will be more. I shall soon purchase some Hare Off, an organic product that really works in keeping hares and other critters out of the garden. Even if the hare(s) do some damage, I will never do anything to harm them. I’m only too happy to see my old friends back after all these years. Be fruitful, hares, and prosper.

My seminar consisted of a Friday night slide show and discussion, complete with specimens that I had brought from home. This was followed by a field trip on Saturday morning. I spent much of Friday driving around and walking through potential sites. And as expected, the best place I found was not out in the wilds of northern Maine, but rather on property owned by the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife (DIF&W), in downtown Greenville. Here, the ground had recently been bulldozed, allowing for a host of wild plants to self-seed. Also, a seasonal stream flowed through the site, adding more edible plant habitat. On that one site, we found winter cress (a mustard-like plant with delicious, broccoli-like flower buds), jewelweed, wild mint, wild evening primrose (we dug some of the edible roots), dandelions and red dock. Several other plants of interest grew there as well, mostly wildflowers. After leaving the DIF&W site, we headed for Little Moose Township, in the big woods. Here, except for where loggers had constructed tote roads, there were no wild edibles. But along the roads, where the sun shone bright, and just inside the woods where there was dappled sunlight, we found enough edible plants to make our trip interesting. The contrast between these two sites proved my point wonderfully. Nothing much except trees and mosses grow in dark, thick woods. Add the human element, with roads, woodyards and so forth, and plants suddenly find a place to take hold. So in this instance, anyway, we humans are not the problem. We are the enablers.

Nobody plants dandelions (with one rare exception, which we’ll discuss later). Instead, these “weeds” arrive unbidden, without so much as a by your leave. That infuriates many homeowners, especially those who love tidy, perfectly green lawns. And so hands-on types attack dandelions with special diggers, while the bulk of the dandelion haters apply chemicals. Either way, the dandelion gets a bad go of it. That one exception mentioned above? Well that was me, of course. I love dandelions, both to eat and to look at. Many years ago, when my woodland yard had no dandelions, I took things into my own hands and gathered a bunch of ripe seedheads. Then I ran around waving them about, so that the parachute seeds floated on the breeze, in effect seeding my place with dandelions. Now I needn’t travel to dig my spring greens, and I have the pretty blossoms to look at, right here at home. Mushrooms, another beneficial invader of the well-manicured lawn, are next on the hit list. One of my favorite gardening magazines just ran a piece about how to eradicate fairy ring mushrooms. Again, I puzzle over this. Why would anyone want to get rid of perfectly fine, edible mushrooms? What’s more, fairy rings last a long time, giving a new and expanded flush each year. I often pick mushrooms in other places and let them rot on my lawn, in an attempt to establish spores. I don’t yet have fairy ring mushrooms, but I keep hoping. I have introduced many more “weeds” to my place, plants that everyone else appears to loathe. You could say I have a weird lawn, given the amount of weeds and other unpopular herbs that I have gone to lengths to establish. But for me, that’s the soul of enjoying nature. The more the merrier. Although I don’t really expect anyone to follow my example, one thing is for sure. That is, it’s easier to cooperate with nature rather than to try and fight her. Nobody, no matter how fastidious, dedicated or diligent, will ever totally keep the “weeds” at bay.

I can remember when fiddleheads (the immature fronds of ostrich fern, Pteretis pensylvanica) were vastly more popular than they are today. That was before supermarkets carried such a wide variety of fresh vegetables. I believe that today, most people are so used to buying food that they look at foraged foods as quaint--perhaps unnecessary. Also, the socio-economic makeup of Maine has changed dramatically. In past years, the average income was considerably less, and many people lived close to the land. Rural areas were truly rural, and things like fiddleheads, dandelions and other wild plants were eagerly sought after. Today, most folks don’t have time to poke around wet areas and streamsides, looking for potable vegetables. I remember when you couldn’t go to town in May, but what someone would ask, “Did you get your fiddleheads yet?” Indeed, the person to pick that first mess of fiddleheads did much to enlarge his or her status in the community. It was assumed, and rightly so, that most everyone liked fiddleheads. I still make those early-season trips, hoping beyond hope to find those first, small, tightly-packed ferns sticking up from the ground. And now, when I pick my first fiddleheads, there is nobody to tell about it. Nobody cares. But perhaps, just maybe, someone still cares. Maybe that someone is you.

I’m referring to wild, edible plants, the kind that foragers seek in spring. Each plant breaks ground, grows and matures according to a pre-set timetable. Each in its own time and nothing can change that. In other words, dandelions always present themselves well ahead of ostrich fern fiddleheads and jewelweed always reaches its prime just after fiddleheads. Never, ever, will we see jewelweed ahead of dandelions, for instance. The problem this year, though, is that even dandelions are late because of the damp, cold weather. And until dandelions prevail, the other plants must wait in line, as it were. In a normal year, this late-arriving spring would cause some consternation. This year, though, is anything but normal. Maine remains in an enforced lockdown, with stores and restaurants shuttered, movie theaters closed and people of faith constrained from worshiping together. We are allowed to participate in outdoor activities as long as we stay well apart from one another, and foraging ranks as a permitted activity. The problem is, there is little to forage. By late April and early May, we should have a lengthy list of wild goodies to harvest. However, cold and frequent snow have conspired to slow plant’s metabolisms, thus retarding their growth until conditions improve. Here’s another troublesome thing about this dearth of wild, edible plants. I grow my own vegetables and can and freeze them. But my homegrown produce from last year has almost run out. Normally, I would make a seamless transition from canned and frozen to fresh-picked, wild foods. By now, totally wild meals would be the order of the day. That hasn’t happened yet, due to lingering winter conditions. Sure, fresh vegetables are available from the store. I always balked at commercially-grown produce, though. Mostly, things such as lettuce, cucumbers and green beans are well past their peak by the time they reach supermarket shelves. Besides that, who knows what kinds of pesticides were used in growing them? Also, watching people pick up vegetables, inspect them and then put them back on the shelf, always made me uncomfortable. What might those people have on their hands? Do I really want to eat what they just pawed over? The answer is a resounding, “No.” That’s why wild, edible plants are so important. Soon, things will and must change. May could see a continuation of the current weather pattern. Even so, the sun grows higher with each passing day and in that we place our hope for an end to cold temperatures and snow showers. When the change finally occurs, I wager that we’ll be like colts let out of the barn for the first time in spring. As soon as we can go afield, minus heavy clothes and gloves, all will be forgotten. So take heart. Though spring eludes us at the moment, the end draws near. We’ve weathered similar conditions in the past and we’ll weather the current situation too.

First are Tom turkeys, gobbling madly to their prospective mates. The turkey utters his spiel in a long string of high-pitched notes that descend at the end. This lasts until well into mid-morning. Imagine trying to sleep with a dozen or so turkeys just outside your bedroom window. It’s nearly impossible. I need to remind myself to go to bed extra-early now, to make up for lost sleep in the morning. Next, are the various woodpeckers. Male woodpeckers drum on anything that will resonate, in order to attract and hopefully, impress a mate. The ice storm of 1998 did much to create drumming trees, too. Dead poplars and half-dead maples resonate nicely, much to the woodpecker’s delight. Some sounds are less intrusive, even pleasant. Wood frogs, what I consider the true harbinger of spring, lend their staccato, quacking sound to still afternoon and evenings. Spring peepers, thousands of them, make a high-pitched din that quickly lulls the listener. Canada geese fly past early and late in the day, and during migration, at night. Just one pair of geese can make an awful racket. But unlike turkeys and woodpeckers, the geese soon pass, and are as soon forgotten.

Yet, I wonder if it is what I hope it is. Speculation will not suffice, not when the road I must negotiate each day is nearly impassable. This requires a quick jog out to the main road, to see if my dream has indeed come true. And there I see Santa Claus, the Easter Bunny and every other mythical, benevolent being, all wrapped up in one, in the form of a bearded man driving a big, yellow road grader. The road grader has come. Rejoice and be glad. This guy is from the government, and he is here to help.

This particular stream lies in a pastoral setting. Fields bound it, and hedgerows divide the fields from the stream. Here’s an account of my time there on a day in May. I began fishing and while Mayflies were absent from the water, I knew what kind of flies would, or should be hatching and acted accordingly. My guess was correct, because trout bit madly, one after another. After having my fill of catching fish, it was time to head home. A pair of bobolinks caught my attention. These were perched atop some of last year’s goldenrod stalks. It had been a while since I saw a bobolink, so these were a real treat. I smelled a familiar fragrance, and looked around for the source. It was honeysuckle, some of the first of the year to bloom. I got back to my car and lo and behold, found a Mayfly inside, exactly the kind that I had expected to see on the stream. I let the fly out, and it went on its way none the worse for wear. I passed another stream on the way home, and couldn’t resist stopping and taking a few casts. The trout did not cooperate, but I noticed a lush stand of wild mint, what I generically call, “brook mint.” This I picked and stuffed in my pocket so that I could enjoy the fragrance as I fished. I made a mental note to return later in summer, when the mint is taller. When I got home, I noticed that blossoms on some of the apple trees out back had opened up into flowers. And so ended my stolen day of bliss.

But that seems to me nothing more than wishful thinking, since what bird, knowing that a driving Nor’easter was in the offing, would come to Maine now, rather than waiting for the storm to subside? Besides that, phoebes are flycatchers, meaning that they subside upon flying insects, mostly caught on the wing. But insects do not fly about during Nor’easters. Personally, I don’t think phoebes have the sense that God gave a pump handle. They relentlessly continue to build their mud nests above the trim on my back door, despite me removing it on a regular basis. Phoebes don’t learn from past errors. While I enjoy watching phoebes catch mosquitoes, blackflies and other nuisance insects, I resent the mess they make. Bird splatter on my car windshield and on garden tools and machines stored in my shed do not make predispose me toward these messy birds. And yet, phoebes have a disarming way about them. How can anyone not smile when watching a phoebe on a fencepost, twitching its tail up and down in a rhythmical motion? The arrival of the phoebe marks the official beginning of spring, at least for me. Here’s something about another familiar animal that we humans credit with having a kind of innate intelligence that doesn’t really exist. Beavers, those ubiquitous dam builders, have an inbred knowledge of how to build stick dams. That’s a fact that no one can dispute. But after that, beavers don’t know how to pour water out of a boot with instructions written on the heel. We call beavers, “nature’s engineers,” a well-deserved title as per their dam-building skills. But after that, the toothy mammals put an end to any anthropomorphic meanderings. For instance, most of us have seen where beavers have felled trees, trees that they would later peel and cut into sections. We quite naturally assume that beavers are skilled woodcutters. But in reality they are not. Beavers have not a clue where a tree will fall. As proof, those who spend time around wetlands and beaver ponds can testify to finding dead beavers, crushed by the tree they cut. Sorry to shatter any romantic notions regarding beavers, but they really don’t have any sense of reasoning. This is like the beloved, pet dog, who the loving owner says is, “almost human.” Well, Fido is “almost human,” until he rolls on a fresh cow patty or dead and decomposing chicken. The worst of it is, the dog thinks it has done some admirable thing, as evidenced by it grinning and happily wagging its tail. Don’t get me wrong. I love our birds, fish and critters. But at the same time, I am familiar enough with them to not assign qualities that they don’t possess. That’s just the reality of it.

The commissioner of the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife has opened the fishing season on rivers, streams and brooks early. This went into effect on Friday, March 20. The department is to be congratulated on this thoughtful move. It has allowed Mainers who, being pent up in their homes with no place to go, to get out away from others and go fishing. This idea of having the opening day on April 1 is purely based upon tradition rather than any biological reason. Fisheries managers whom I have spoken with over the years always tell me the same thing; “it’s tradition.”

To that end I will continue arguing for a push-back on the opening day. We Maine anglers deserve that much. Besides that, the opening-day tradition has long fallen by the wayside. The number of serious stream anglers has decreased considerably over the last few decades. This is directly attributable to people having more disposable income. Whereas once, few people owned boats and at that, these were smallish watercraft, in the 12- to 14-foot range, today most serious anglers own larger boats. And people with larger boats seek larger fish, which explains the current lack of participation for brook and stream fishing. Those of a certain age may well recall when, during April school vacation week, every stream crossing would have two or three bicycles leaning against the bridge. Children loved to fish and when given the opportunity, took to the brooks and streams in droves. I recall purposely avoiding the places where the children liked to fish, figuring that I can get out any time, but the youngsters are bound to remain in school. My feeling was just to let them have their fun, with no competition from me. Today, though, children are more, “sophisticated.” Indoor entertainment, mostly computer-based activities, have largely supplanted the urge to get outdoors and go fishing. It’s a sad commentary, and one that will probably never change. As for older children, me for example, walking along a bubbling brook, probing each riffle and undercut bank for hidden trout, still has its appeal. To that end, I went out last Friday and caught my limit of native brook trout. These I took home and lovingly cared for. Then I had them for supper, no cornmeal, no flour, just a bit of salt. The flesh of these speckled jewels is the most delicate of any fish. You cannot buy such as this from the grocery store. Instead, you must get out and catch them yourself. So thank you Fish & Wildlife commissioner Camuso. She and Governor Mills have done a kind and good thing for anxious Mainers. The department has also moved to allow those without fishing licenses to go afield until the end of April, another thoughtful move in this time of worry and strife. Stay safe and healthy. And if the desire animates you, get out and catch some trout from our countless brooks and streams. Good luck.

|

AuthorAn avid writer and naturalist, Tom writes four regular columns and a multitude of features. He wrote a long running award winning column "Waldo County Outdoors" and a garden column for Courier Publications Archives

November 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed